Azure Cache Serialization (with JSON!)

• CommentsI’m building an Azure service that will rely somewhat heavily on Azure in-role caching; this post documents some of my findings.

Serialization Options

Azure caching is a form of distributed cache, so it uses serialization to store object instances. When you install the NuGet Azure Caching package, you get a .config that looks like this:

<dataCacheClients>

<dataCacheClient name="default">

</dataCacheClient>

</dataCacheClients>Most of the settings are documented on MSDN.

With the default settings like this, Azure Caching will use NetDataContractSerializer. As we’ll see, this is not exactly the most efficient setting.

First, let’s consider alternative serializers. You can add a serializationProperties element to your config and specify BinaryFormatter as such:

<dataCacheClients>

<dataCacheClient name="default">

<serializationProperties serializer="BinaryFormatter" />

</dataCacheClient>

</dataCacheClients>You can also specify a custom serializer as such:

<dataCacheClients>

<dataCacheClient name="default">

<serializationProperties serializer="CustomSerializer" customSerializerType="MyType,MyAssembly" />

</dataCacheClient>

</dataCacheClients>There’s also another knob you can tweak: you can turn on compression (i.e., DeflateStream) by setting isCompressionEnabled as such:

<dataCacheClients>

<dataCacheClient name="default" isCompressionEnabled="true">

</dataCacheClient>

</dataCacheClients>Under the Covers

There are actually seven different serializers that can be used, as of the time of this writing. Each serialized object is prepended with a tiny prefix that identifies the serializer used and whether the object stream is compressed.

If you specify CustomSerializer for the serializer type, then your custom serializer is always used. However, if you’re using NetDataContractSerializer or BinaryFormatter, then Azure Caching automatically switches to optimized serializers if your objects are already binary arrays (byte[]), primitive types (string, int, uint, long, ulong, short, ushort, double, float, decimal, bool, byte, sbyte), or SessionStoreProviderData.

Note that the prefix for a custom serializer only indicates that a custom serializer was used; it does not store the actual type of the custom serializer.

Changing Serialization Options

Since Azure Caching stores a prefix, you can change the isCompressionEnabled during a rolling upgrade without any problems. Similarly, you can change serializer back and forth between NetDataContractSerializer and BinaryFormatter.

You can also change serializer to CustomSerializer during a rolling upgrade, but you can’t change back. This is because Azure Caching will not use a custom deserializer unless it is configured to use a custom serializer.

Also, note that once a custom serializer is specified, it is always used. So your custom serializer should at least have versioning logic built-in; otherwise you won’t ever be able to change your custom serialization during a rolling upgrade.

Performance

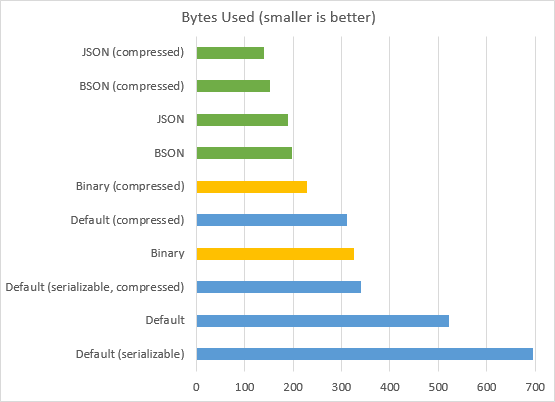

I wrote up a simple test to compare these serializers and see what kind of effect compression has. This test only covers the actual serialization used by Azure Caching without actually putting the items in the cache.

In my Azure service, I’ll be mostly storing small custom objects with 3-4 string properties, so that’s what I’m testing here. The type looks like this:

public class MyTypeNSer

{

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string LastName { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

}There’s a matching type called MyTypeYSer which is identical except it is marked with [Serializable], which is required by BinaryFormatter.

All instances have FirstName set to "Christopher", LastName set to "Dombrowski", and Description set to "This is a generic string solely for the purpose of searching.". This is representative of the kinds of data I’ll be storing in the cache in my project; if your object structure is quite different, then your results may be different as well.

I ran through serializing with each of the built-in serializers, as well as JSON and BSON (binary JSON) serializers from JSON.NET; and with/without compression for each one. Each test serialized the object instance and then deserialized it, and compared the deserialized object with the original to ensure there were no errors.

First, the default serializer (NetDataContractSerializer), which is XML-based. When serialized, the MyTypeNSer instance took up 521 bytes (312 compressed). The serialized data looks like this:

<MyTypeNSer z:Id="1" z:Type="AzureCacheSizeTest.MyTypeNSer" z:Assembly="AzureCacheSizeTest, Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null" xmlns="http://schemas.datacontract.org/2004/07/AzureCacheSizeTest" xmlns:i="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns:z="http://schemas.microsoft.com/2003/10/Serialization/"><Description z:Id="2">This is a generic string solely for the purpose of searching.</Description><FirstName z:Id="3">Christopher</FirstName><LastName z:Id="4">Dombrowski</LastName></MyTypeNSer>During my testing, I discovered that the default serializer acts differently when used on a [Serializable] type. Instead of serializing the properties directly, it looks like it serializes their backing fields:

<MyTypeYSer z:Id="1" z:Type="AzureCacheSizeTest.MyTypeYSer" z:Assembly="AzureCacheSizeTest, Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null" xmlns="http://schemas.datacontract.org/2004/07/AzureCacheSizeTest" xmlns:i="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns:z="http://schemas.microsoft.com/2003/10/Serialization/"><_x003C_Description_x003E_k__BackingField z:Id="2">This is a generic string solely for the purpose of searching.</_x003C_Description_x003E_k__BackingField><_x003C_FirstName_x003E_k__BackingField z:Id="3">Christopher</_x003C_FirstName_x003E_k__BackingField><_x003C_LastName_x003E_k__BackingField z:Id="4">Dombrowski</_x003C_LastName_x003E_k__BackingField></MyTypeYSer>In this case (with automatic backing fields), this bloats the serialized size to 695 bytes (340 compressed). Here’s a side-by-side comparison of how the data looks:

<MyTypeNSer z:Id="1" z:Type="AzureCacheSizeTest.MyTypeNSer" z:Assembly="AzureCacheSizeTest, Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null" xmlns="http://schemas.datacontract.org/2004/07/AzureCacheSizeTest" xmlns:i="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns:z="http://schemas.microsoft.com/2003/10/Serialization/"><Description z:Id="2">This is a generic string solely for the purpose of searching.</Description><FirstName z:Id="3">Christopher</FirstName><LastName z:Id="4">Dombrowski</LastName></MyTypeNSer>

<MyTypeYSer z:Id="1" z:Type="AzureCacheSizeTest.MyTypeYSer" z:Assembly="AzureCacheSizeTest, Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null" xmlns="http://schemas.datacontract.org/2004/07/AzureCacheSizeTest" xmlns:i="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns:z="http://schemas.microsoft.com/2003/10/Serialization/"><_x003C_Description_x003E_k__BackingField z:Id="2">This is a generic string solely for the purpose of searching.</_x003C_Description_x003E_k__BackingField><_x003C_FirstName_x003E_k__BackingField z:Id="3">Christopher</_x003C_FirstName_x003E_k__BackingField><_x003C_LastName_x003E_k__BackingField z:Id="4">Dombrowski</_x003C_LastName_x003E_k__BackingField></MyTypeYSer>Next up is the BinaryFormatter. As expected, the binary serializer results in a smaller object size: 325 bytes (229 compressed). The serialized data looks like this (using \xx for binary hex values):

\00\01\00\00\00\FF\FF\FF\FF\01\00\00\00\00\00\00\00\0C\02\00\00\00IAzureCacheSizeTest, Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=null\05\01\00\00\00\1DAzureCacheSizeTest.MyTypeYSer\03\00\00\00\1A<FirstName>k__BackingField\19<LastName>k__BackingField\1C<Description>k__BackingField\01\01\01\02\00\00\00\06\03\00\00\00\0BChristopher\06\04\00\00\00\0ADombrowski\06\05\00\00\00=This is a generic string solely for the purpose of searching.\0B

Finally, I wanted to try JSON, since practically any modern Azure service already has a reference to JSON.NET anyway. JSON performed quite well: 189 bytes (140 compressed). The serialized instance looks like this:

{"$type":"AzureCacheSizeTest.MyTypeNSer, AzureCacheSizeTest","FirstName":"Christopher","LastName":"Dombrowski","Description":"This is a generic string solely for the purpose of searching."}However, I was also aware that JSON.NET supports BSON (Binary JSON), so I was curious to see whether there were any further space savings that I could squeeze out. BSON was slightly less efficient than JSON, weighing in at 197 bytes (152 compressed). As it turns out, BSON is not a “compressed JSON” format as much as it is a “fast and traversable” JSON, as described in their FAQ. For completeness, here’s the same instance as it appears in BSON:

\C5\00\00\00\02$type\002\00\00\00AzureCacheSizeTest.MyTypeNSer, AzureCacheSizeTest\00\02FirstName\00\0C\00\00\00Christopher\00\02LastName\00\0B\00\00\00Dombrowski\00\02Description\00>\00\00\00This is a generic string solely for the purpose of searching.\00\00

Note that BSON would perform better than JSON if I was storing more binary data, e.g., profile images of the people. But my use case is just strings, and there JSON wins out.

The Graph

Here’s all the results in a more visual format, from most efficient to least efficient:

Lessons Learned

At the very least, you should turn on compression (a 40% savings over the default settings). You can do this at any time, even with a rolling upgrade.

Also consider compressed BinaryFormatter (a 55% savings). Unfortunately, BinaryFormatter does require your types to be [Serializable], which can be tedious or impossible. Switching to BinaryFormatter can also be done with a rolling upgrade.

For myself, I’m going all-out with a JSON-based custom serializer that handles its own versioning. This offers the most compact representation of the ones I tried (>70%, or 3.5 times smaller). However, once you switch to CustomSerializer, you can never switch back with a rolling upgrade (you’d need to fully stop your service, clearing the cache, and then start again).

Note on JSON and Type Names

By default, JSON doesn’t store the type names of the objects it’s serializing. If the type name isn’t stored, the deserializer can’t know the type of the serialized object, and it will just create a JObject and return that.

You can instruct JSON.NET to emit type names. I chose TypeNameHandling.Auto, which means that the type name is only serialized if it doesn’t match the declared type. This meant I also had to call the JsonSerializer.Serialize overload that took a Type argument, passing typeof(object). This sounds weird, but what I’m actually doing is explicitly telling JSON.NET that my instance was declared as type object and therefore needs a type name emitted at the root.

The Code

This is a simple console app up on Gist that displays the sizes to the console and trace-writes the actual streams to the debugger.

| using System; | |

| using System.Collections; | |

| using System.Diagnostics; | |

| using System.IO; | |

| using System.IO.Compression; | |

| using System.Linq; | |

| using System.Runtime.Serialization; | |

| using System.Runtime.Serialization.Formatters.Binary; | |

| using System.Text; | |

| using Comparers; | |

| using Newtonsoft.Json; | |

| using Newtonsoft.Json.Bson; | |

| namespace AzureCacheSizeTest | |

| { | |

| public class MyTypeNSer | |

| { | |

| public string FirstName { get; set; } | |

| public string LastName { get; set; } | |

| public string Description { get; set; } | |

| } | |

| [Serializable] | |

| public class MyTypeYSer | |

| { | |

| public string FirstName { get; set; } | |

| public string LastName { get; set; } | |

| public string Description { get; set; } | |

| } | |

| class Program | |

| { | |

| public static readonly IFullComparer<MyTypeYSer> ComparerYSer = Compare<MyTypeYSer>.OrderBy(x => x.FirstName).ThenBy(x => x.LastName).ThenBy(x => x.Description); | |

| public static readonly IFullComparer<MyTypeNSer> ComparerNSer = Compare<MyTypeNSer>.OrderBy(x => x.FirstName).ThenBy(x => x.LastName).ThenBy(x => x.Description); | |

| static void Main(string[] args) | |

| { | |

| var yser = new MyTypeYSer { FirstName = "Christopher", LastName = "Dombrowski", Description = "This is a generic string solely for the purpose of searching." }; | |

| var nser = new MyTypeNSer { FirstName = "Christopher", LastName = "Dombrowski", Description = "This is a generic string solely for the purpose of searching." }; | |

| Console.Write("Default: "); | |

| TestDefault(nser, CompressionLevel.NoCompression); | |

| Console.Write("Default (compressed): "); | |

| TestDefault(nser, CompressionLevel.Optimal); | |

| Console.Write("Default (serializable): "); | |

| TestDefault(yser, CompressionLevel.NoCompression); | |

| Console.Write("Default (serializable, compressed): "); | |

| TestDefault(yser, CompressionLevel.Optimal); | |

| Console.Write("Binary: "); | |

| TestBinary(yser, CompressionLevel.NoCompression); | |

| Console.Write("Binary (compressed): "); | |

| TestBinary(yser, CompressionLevel.Optimal); | |

| Console.Write("JSON: "); | |

| TestJson(nser, CompressionLevel.NoCompression); | |

| Console.Write("JSON (compressed): "); | |

| TestJson(nser, CompressionLevel.Optimal); | |

| Console.Write("BSON: "); | |

| TestBson(nser, CompressionLevel.NoCompression); | |

| Console.Write("BSON (compressed): "); | |

| TestBson(nser, CompressionLevel.Optimal); | |

| Console.ReadKey(); | |

| } | |

| private static void Test(object value, Action<Stream, object> serialize, Func<Stream, object> deserialize, CompressionLevel compression) | |

| { | |

| try | |

| { | |

| var output = new MemoryStream(); | |

| if (compression == CompressionLevel.NoCompression) | |

| serialize(output, value); | |

| else | |

| { | |

| using (var compressStream = new DeflateStream(output, compression)) | |

| { | |

| serialize(compressStream, value); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| output.Flush(); | |

| var data = output.ToArray(); | |

| Console.WriteLine(data.Length); | |

| Trace.WriteLine(""); | |

| Trace.WriteLine(string.Join("", data.Select(x => | |

| ((x >= 32 && x <= 91) || (x >= 93 && x <= 126)) ? new string(new [] { (char)x }) : (@"\" + x.ToString("X2"))))); | |

| Trace.WriteLine(string.Join("", data.Select(x => x.ToString("X2")))); | |

| var input = new MemoryStream(data); | |

| object result; | |

| if (compression == CompressionLevel.NoCompression) | |

| result = deserialize(input); | |

| else | |

| { | |

| using (var decompressStream = new DeflateStream(input, CompressionMode.Decompress)) | |

| { | |

| result = deserialize(decompressStream); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| var comparer = (value is MyTypeNSer) ? ComparerNSer as IEqualityComparer : ComparerYSer; | |

| if (!comparer.Equals(value, result)) | |

| Console.WriteLine("Compare failed!"); | |

| } | |

| catch (Exception ex) | |

| { | |

| Console.WriteLine(ex.Message); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| public static void TestDefault(object value, CompressionLevel compression) | |

| { | |

| var serializer = new NetDataContractSerializer(); | |

| Test(value, serializer.WriteObject, serializer.ReadObject, compression); | |

| } | |

| private static void TestBinary(object value, CompressionLevel compression) | |

| { | |

| var serializer = new BinaryFormatter(); | |

| Test(value, serializer.Serialize, serializer.Deserialize, compression); | |

| } | |

| private static void TestJson(object value, CompressionLevel compression) | |

| { | |

| var serializer = JsonSerializer.Create(new JsonSerializerSettings | |

| { | |

| TypeNameHandling = TypeNameHandling.Auto, | |

| NullValueHandling = NullValueHandling.Ignore, | |

| }); | |

| Test(value, | |

| (stream, val) => | |

| { | |

| using (var textWriter = new StreamWriter(stream, new UTF8Encoding(false))) | |

| using (var writer = new JsonTextWriter(textWriter)) | |

| serializer.Serialize(writer, val, typeof(object)); | |

| }, | |

| stream => | |

| { | |

| using (var textReader = new StreamReader(stream, Encoding.UTF8, false)) | |

| using (var reader = new JsonTextReader(textReader)) | |

| return serializer.Deserialize(reader); | |

| }, | |

| compression); | |

| } | |

| private static void TestBson(object value, CompressionLevel compression) | |

| { | |

| var serializer = JsonSerializer.Create(new JsonSerializerSettings | |

| { | |

| TypeNameHandling = TypeNameHandling.Auto, | |

| NullValueHandling = NullValueHandling.Ignore, | |

| }); | |

| Test(value, | |

| (stream, val) => | |

| { | |

| using (var writer = new BsonWriter(stream)) | |

| serializer.Serialize(writer, val, typeof(object)); | |

| }, | |

| stream => | |

| { | |

| using (var reader = new BsonReader(stream)) | |

| return serializer.Deserialize(reader); | |

| }, | |

| compression); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } |