A Tour of Task, Part 0: Overview

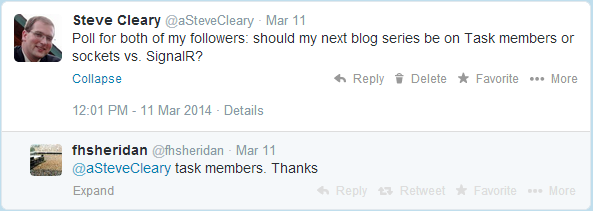

• CommentsI recently posted a poll on The Twitter; here it is with all the responses:

It’s unanimous! This post is the first in a series that will take a look at all the Task members (as of .NET 4.5).

What is a “Task”

A Task is an object representing some operation that will complete in the future. In other languages, this same concept is commonly called a “Future” or a “Promise”. In C#, tasks may represent some code that is running, or they may represent some future event (e.g., a timer firing).

A Bit of Task History

One of the biggest stumbling blocks to developers learning async is actually the Task type itself. Most developers fall into one of two categories:

- Developers who have used

Taskand the TPL (Task Parallel Library) since it was introduced in .NET 4.0. These developers are familiar withTaskand how it is used in parallel processing. The danger that these developers face is thatTask(as it is used by the TPL) is pretty much completely different thanTask(as it is used byasync). - Developers who have never heard of

Taskuntilasynccame along. To them,Taskis just a part ofasync- one more (fairly complicated) thing to learn. “Continuation” is a foreign word. The danger that these developers face is assuming that every member ofTaskis applicable toasyncprogramming, which is most certainly not the case.

The async team at Microsoft did consider writing their own “Future” type that would represent an asynchronous operation, but the Task type was too tempting. Task actually did support promise-style futures (somewhat awkwardly) even in .NET 4.0, and it only took a bit of extension for it to support async fully. Also, by merging this “Future” with the existing Task type, we end up with a nice unification: it’s trivially easy to kick off some operation on a background thread and treat it asynchronously. No conversion from Task to “Future” is necessary.

The downside to using the same type is that it does create some developer confusion. As noted above, developers who have used Task in the past tend to try to use it the same way in the async world (which is wrong); and developers who have not used Task in the past face a bewildering selection of Task members, almost all of which should not be used in the async world.

So, that’s how we got to where we are today. This blog series will go through all the various Task members (yes, all of them), and explain the purpose behind each one. As we’ll see, the vast majority of Task members have no place in async code.

Two Types of Task

There are two types of tasks. The first type is a Delegate Task; this is a task that has code to run. The second type is a Promise Task; this is a task that represents some kind of event or signal. Promise Tasks are often I/O-based signals (e.g., “the HTTP download has completed”), but they can actually represent anything (e.g., “the 10-second timer has expired”).

In the TPL world, most tasks were Delegate Tasks (with some support for Promise Tasks). When code does parallel processing, the various Delegate Tasks are divided up among different threads, which then actually execute the code in those Delegate Tasks. In the async world, most tasks are Promise Tasks (with some support for Delegate Tasks). When code does an await on a Promise Task, there is no thread tied up waiting for that task to complete.

In the past, I’ve used the terms “code-based Task” and “event-based Task” to describe the two kinds of tasks. In this series, I will try to use the terms “Delegate Task” and “Promise Task” to distinguish the two.