A Tour of Task, Part 3: Status

• CommentsStatus

TaskStatus Status { get; }If you view a Task as a state machine, then the Status property represents the current state. Different types of tasks take different paths through the state machine.

As usual, this post is just taking what Stephen Toub already said, expounding on it a bit, and drawing some ugly pictures. :)

Delegate Tasks

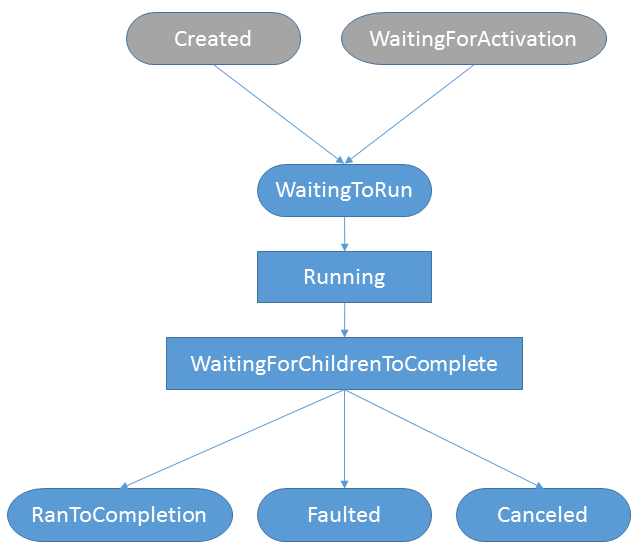

Delegate Tasks follow the basic pattern in the image below:

Usually, Delegate Tasks are created via Task.Run (or Task.Factory.StartNew), and enter the state machine at the WaitingToRun state. WaitingToRun means that the task is associated with a task scheduler, and is just waiting its turn to run.

Entering at the WaitingToRun state is the normal path for Delegate Tasks, but there are a couple of other possibilities.

If a Delegate Task is started with the task constructor, then it starts in the Created state and only moves to the WaitingToRun state when you assign it to a task scheduler via Start or RunSynchronously.

If a Delegate Task is a continuation of another task, then it starts in the WaitingForActivation state and automatically moves to the WaitingToRun state when that other task completes.

The task is in the Running state when the delegate of the Delegate Task is actually executing. When it’s done, the task proceeds to the WaitingForChildrenToComplete state until its children are all completed. Finally, the task ends up in one of the three final states: RanToCompletion (successfully), Faulted, or Canceled.

Remember that since Delegate Tasks represent running code, it’s quite possible that you may not see one or more of these states. For example, it’s possible to queue some very fast work to the thread pool and have that task already completed by the time it’s returned to your code.

Also, this state machine can be short-circuited at any point if the task is canceled. It is possible for the task to be canceled before it enters the Running state, and thus not even execute its delegate.

Promise Tasks

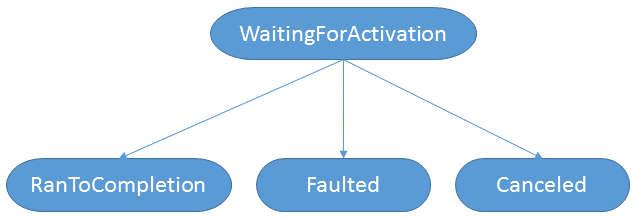

Promise Tasks have a much simpler state machine:

This diagram is slightly simplified; technically, Promise Tasks can enter the WaitingForChildrenToComplete state. However, this is rather non-intuitive and for this reason tasks created for async use usually specify the DenyChildAttach flag.

It is natural to speak of I/O-based operations as “running” or “executing”, e.g., “the HTTP download is currently running”. However, there is no actual CPU code to be run, so Promise Tasks (such as an HTTP download task) will never enter the WaitingToRun or Running states. And yes, this means that a Promise Task may end in the RanToCompletion state without ever actually running. Well, it is what it is…

All Promise Tasks are created “hot”, meaning that the operation is in progress. The confusing part is that this “in-progress” state is actually called WaitingForActivation.

For this reason, I try to avoid using the terms “running” or “executing” when talking about Promise Tasks; instead, I prefer to say that “the operation is in progress”.

Status Properties

Task has a few convenience properties for determining the final state of a task:

bool IsCompleted { get; }

bool IsCanceled { get; }

bool IsFaulted { get; }IsCanceled and IsFaulted map directly to the Canceled and Faulted states, but IsCompleted is tricky. IsCompleted does not map to RanToCompletion; rather, it is true if the task is in any final state. In other words:

| Status | IsCompleted |

IsCanceled |

IsFaulted |

|---|---|---|---|

| other | |||

RanToCompletion |

|||

Canceled |

|||

Faulted |

Conclusion

As interesting as these state properties all are, they are hardly ever actually used (except for debugging). Both asynchronous and parallel code do not normally use Status or the three convenience properties; instead, the normal usage is to wait for the tasks to complete and extract the results.