There Is No Thread

• CommentsThis is an essential truth of async in its purest form: There is no thread.

The objectors to this truth are legion. “No,” they cry, “if I am awaiting an operation, there must be a thread that is doing the wait! It’s probably a thread pool thread. Or an OS thread! Or something with a device driver…”

Heed not those cries. If the async operation is pure, then there is no thread.

The skeptical are not convinced. Let us humor them.

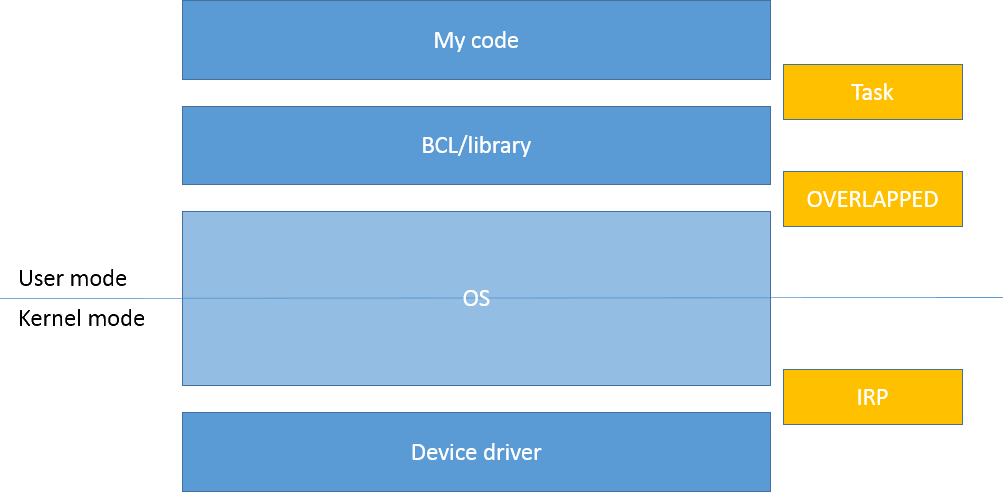

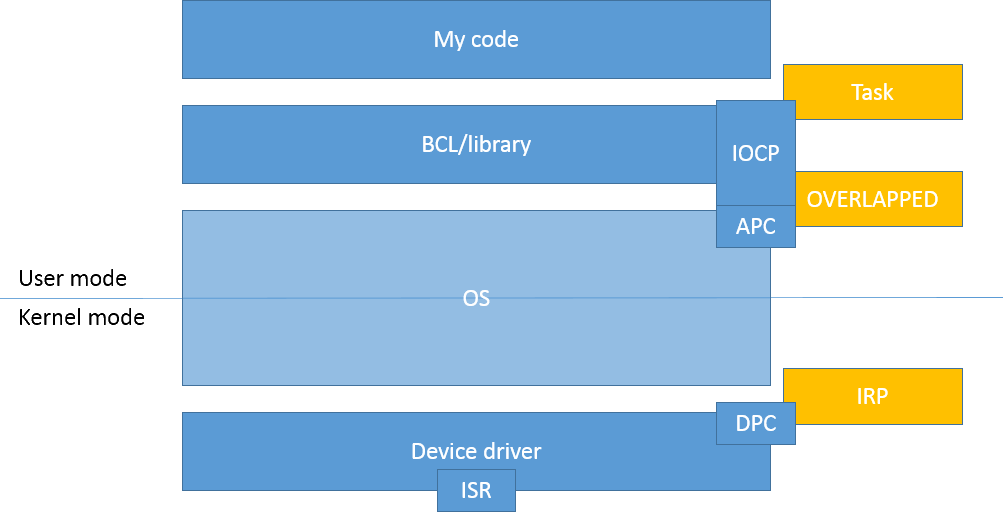

We shall trace an asynchronous operation all the way to the hardware, paying particular attention to the .NET portion and the device driver portion. We’ll have to simplify this description by leaving out some of the middle-layer details, but we shall not stray from the truth.

Consider a generic “write” operation (to a file, network stream, USB toaster, whatever). Our code is simple:

private async void Button_Click(object sender, RoutedEventArgs e)

{

byte[] data = ...

await myDevice.WriteAsync(data, 0, data.Length);

}We already know that the UI thread is not blocked during the await. Question: Is there another thread that must sacrifice itself on the Altar of Blocking so that the UI thread may live?

Take my hand. We shall dive deep.

First stop: the library (e.g., entering the BCL code). Let us assume that WriteAsync is implemented using the standard P/Invoke asynchronous I/O system in .NET, which is based on overlapped I/O. So, this starts a Win32 overlapped I/O operation on the device’s underlying HANDLE.

The OS then turns to the device driver and asks it to begin the write operation. It does so by first constructing an object that represents the write request; this is called an I/O Request Packet (IRP).

The device driver receives the IRP and issues a command to the device to write out the data. If the device supports Direct Memory Access (DMA), this can be as simple as writing the buffer address to a device register. That’s all the device driver can do; it marks the IRP as “pending” and returns to the OS.

The core of the truth is found here: the device driver is not allowed to block while processing an IRP. This means that if the IRP cannot be completed immediately, then it must be processed asynchronously. This is true even for synchronous APIs! At the device driver level, all (non-trivial) requests are asynchronous.

To quote the Tomes of Knowledge, “Regardless of the type of I/O request, internally I/O operations issued to a driver on behalf of the application are performed asynchronously”.

With the IRP “pending”, the OS returns to the library, which returns an incomplete task to the button click event handler, which suspends the async method, and the UI thread continues executing.

We have followed the request down into the abyss of the system, right out to the physical device.

The write operation is now “in flight”. How many threads are processing it?

None.

There is no device driver thread, OS thread, BCL thread, or thread pool thread that is processing that write operation. There is no thread.

Now, let us follow the response from the land of kernel daemons back to the world of mortals.

Some time after the write request started, the device finishes writing. It notifies the CPU via an interrupt.

The device driver’s Interrupt Service Routine (ISR) responds to the interrupt. An interrupt is a CPU-level event, temporarily seizing control of the CPU away from whatever thread was running. You could think of an ISR as “borrowing” the currently-running thread, but I prefer to think of ISRs as executing at such a low level that the concept of “thread” doesn’t exist - so they come in “beneath” all threads, so to speak.

Anyway, the ISR is properly written, so all it does is tell the device “thank you for the interrupt” and queue a Deferred Procedure Call (DPC).

When the CPU is done being bothered by interrupts, it will get around to its DPCs. DPCs also execute at a level so low that to speak of “threads” is not quite right; like ISRs, DPCs execute directly on the CPU, “beneath” the threading system.

The DPC takes the IRP representing the write request and marks it as “complete”. However, that “completion” status only exists at the OS level; the process has its own memory space that must be notified. So the OS queues a special-kernel-mode Asynchronous Procedure Call (APC) to the thread owning the HANDLE.

Since the library/BCL is using the standard P/Invoke overlapped I/O system, it has already registered the handle with the I/O Completion Port (IOCP), which is part of the thread pool. So an I/O thread pool thread is borrowed briefly to execute the APC, which notifies the task that it’s complete.

The task has captured the UI context, so it does not resume the async method directly on the thread pool thread. Instead, it queues the continuation of that method onto the UI context, and the UI thread will resume executing that method when it gets around to it.

So, we see that there was no thread while the request was in flight. When the request completed, various threads were “borrowed” or had work briefly queued to them. This work is usually on the order of a millisecond or so (e.g., the APC running on the thread pool) down to a microsecond or so (e.g., the ISR). But there is no thread that was blocked, just waiting for that request to complete.

Now, the path that we followed was the “standard” path, somewhat simplified. There are countless variations, but the core truth remains the same.

The idea that “there must be a thread somewhere processing the asynchronous operation” is not the truth.

Free your mind. Do not try to find this “async thread” — that’s impossible. Instead, only try to realize the truth:

There is no thread.