Portable Class Library Enlightenment / Adaptation

• Comments

Update, 2014-05-07: I have been giving it a lot of thought, and I have decided that the Bait-and-Switch approach described by Paul Betts is a better solution than the one described below. This blog post is retained for historical purposes.

I have a long-standing interest in portable class libraries (PCL), because most of my open-source contributions are widely-applicable libraries (including Comparers, ArraySegments, and of course AsyncEx). This post is an explanation of a technique that I learned from Rx; it’s useful for any PCL that is actually a library (i.e., not a portable application).

Portable class libraries are awesome. Now that NuGet supports them, every library writer should join in!

The Problem

Portable Class Libraries enable you to create a single binary that runs on several (.NET) platforms. Unfortunately, it uses the “least common denominator” approach, which means your PCL is greatly constrained in what it can do. In order to “step outside” these restrictions, you need some way for a platform-specific assembly to provide functionality to your PCL core. The obvious answer is to use inversion of control, but how are the (platform-specific) implementations created and passed to your portable code?

Possible Solutions

There are several ways to do this. Daniel Plaisted has a great blog post that gives an overview of different solutions:

- Manual dependency injection (passing interface implementations into constructors). Daniel’s classic “Disentaglement” demo uses this approach as he describes in his //build/ talk. This is OK if your PCL just has a few large classes (e.g., ViewModels) which are always the “entry point” to your PCL. It’s not so good if your PCL is more of a generic library.

- Real dependency injection. The disadvantage to this approach is that it restricts all users of a PCL to a specific DI provider.

- Service locator (static variables holding the interface implementations). This approach is described in the official MSDN documentation (section “Platform Abstraction”). This requires all code using the PCL to “wire up” its own implementations.

- Platform enlightenment / adaptation libraries (extra assemblies loaded via reflection). This is the approach described in this blog post.

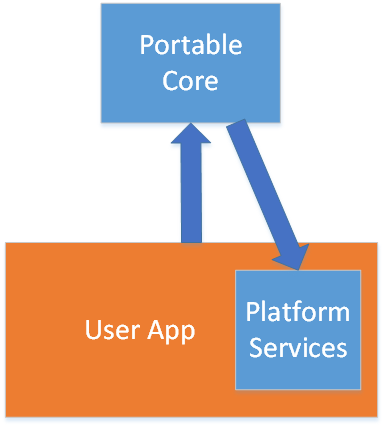

The first three approaches depend on the consumer of the library implementing the platform services (or at least instantiating them) and providing them to the portable library:

This is fine if your PCL is just the core of a portable application, like Daniel’s “Disentanglement” application, where the PCL contains the logic but its “entry points” are just a handful of ViewModels.

But I’m not a fan of this. When I distribute a library, I want users to just add it via NuGet and start using it; requiring “startup” code is a big barrier to adoption.

AFAIK, the Rx team was the first to solve this problem. They describe their “Platform Enlightenment” approach well on their blog (section “Intermezzo - The refactored API surface”). Members of the PCL team have referred to this technique as “Platform Adaptation”.

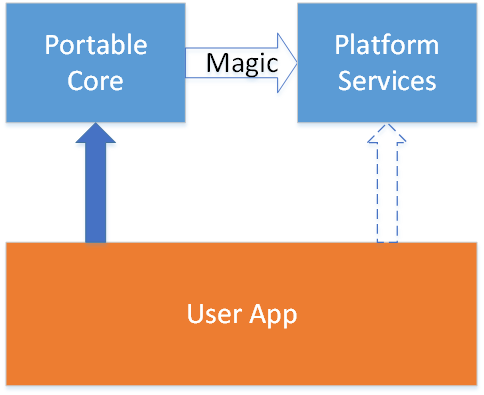

The “dashed arrow” in the diagram above means that the user application has a reference to the platform services library, but does not actually use it. The “magic arrow” does not exist at compile time (so there’s no actual reference there); this will be explained later.

Enabling Enlightenment / Adaptation

You could choose to have all your “platform services” defined in a single interface, but I think it’s cleaner to group your platform services into multiple interfaces. In my code, I call these platform services “enlightenments”. Each “enlightenment” is an interface that has a platform-specific implementation and a default implementation.

Let’s start out with a simple enlightenment called “Bob”. We’ll create a portable class library (called “MyLibrary”) that will act as our Portable Core and define the “Bob” enlightenment interface:

/// Provides Bob-related services.

public interface IBobEnlightenment

{

/// Says "hi"

string SayHi();

}

As an aside, my enlightenment-related types are mostly public, but they are within a special namespace, which indicates to end-users that they are not part of the normal API.

Multiple enlightenment types means that it’s useful to have an “enlightenment provider” (also platform-specific, with a default backup), which just creates instances of the enlightenments. The IEnlightenmentProvider type is defined in the Portable Core:

/// An enlightenment provider, which creates enlightenments on demand.

public interface IEnlightenmentProvider

{

/// Creates an enlightenment of the specified type.

/// <typeparam name="T">The type of enlightenment to create.</typeparam>

T CreateEnlightenment<T>();

}To consume the enlightenments, I use an “enlightenment manager” type, which I just call Enlightenment (also defined in the Portable Core):

/// Provides static members to access enlightenments.

public static class Enlightenment

{

/// Loads the <c>PlatformEnlightenmentProvider</c> if it can be found; otherwise, returns an instance of <see cref="DefaultEnlightenmentProvider"/>.

private static IEnlightenmentProvider CreateProvider();

/// Cached instance of the platform enlightenment provider. This is an instance of the default enlightenment provider if the platform couldn't be found.

private static IEnlightenmentProvider platform;

/// Returns the platform enlightenment provider, if it could be found; otherwise, returns the default enlightenment provider.

public static IEnlightenmentProvider Platform

{

get

{

if (platform == null)

Interlocked.CompareExchange(ref platform, CreateProvider(), null);

return platform;

}

}

/// Cached instance of the Bob enlightenment.

private static IBobEnlightenment bob;

/// Returns the Bob enlightenment.

public static IBobEnlightenment Bob

{

get

{

if (bob == null)

Interlocked.CompareExchange(ref bob, Platform.CreateEnlightenment<IBobEnlightenment>(), null);

return bob;

}

}

... // Other enlightenments just like Bob

}(We’ll come back to the implementation of CreateProvider in a moment).

This setup means that from within my PCL Core, I can consume enlightenments easily:

public class MyPortableClass

{

public MyPortableClass()

{

var word = Enlightenment.Bob.SayHi();

}

}Note that my enlightenment manager implementation is forcing some assumptions on both the enlightenment provider and every enlightenment: they are conceptually singletons, except that they can be constructed multiple times (due to race conditions); in that case, only one instance will be used and all extra instances will be discarded. These are not difficult assumptions to satisfy, but you do need to be aware of them.

The Default Provider

Having a default implementation is important! If an application developer removes your platform-specific assembly from their project’s references, then you will end up at runtime with just your PCL core, and you need to handle that scenario gracefully.

In this case, you’ll need a default provider to step in and provide some kind of reasonable default behavior. I’m not a big fan of NotSupportedException, and I recommend avoiding it as much as possible, but in these cases it may just be necessary.

For our simple “Bob” enlightenment, let’s just return an empty string as our default behavior. Again in the Portable Core:

/// The default enlightenment provider, used when the platform enlightenment provider could not be found.

public sealed class DefaultEnlightenmentProvider : IEnlightenmentProvider

{

T IEnlightenmentProvider.CreateEnlightenment<T>()

{

var type = typeof(T);

if (type == typeof(IBobEnlightenment))

return (T)(object)new BobEnlightenment();

... // other enlightenments.

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

/// The default Bob enlightenment, which does nothing.

public sealed class BobEnlightenment : IBobEnlightenment

{

string IBobEnlightenment.SayHi()

{

return string.Empty;

}

}

}Usually, there’s some form of reflection going on in a default enlightenment instead of being this simple.

The Platform Providers

At this point, we create providers for each of the platforms that need one. So let’s assume that “Bob” wants to say hi from a specific provider, like .NET 4.5.

First, we create a .NET 4.5 assembly. I usually name the project something like “MyLibrary.Enlightenment (NET45)” but ensure the assembly name is just “MyLibrary.Enlightenment”. Then we reference our portable core and define the platform-specific enlightenment provider and enlightenments:

/// The platform enlightenment provider for .NET 4.5.

public sealed class EnlightenmentProvider : IEnlightenmentProvider

{

T IEnlightenmentProvider.CreateEnlightenment<T>()

{

var type = typeof(T);

if (type == typeof(IBobEnlightenment))

return (T)(object)new BobEnlightenment();

... // other enlightenments.

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

private sealed class BobEnlightenment : IBobEnlightenment

{

string IBobEnlightenment.SayHi()

{

return "Hello from .NET 4.5!";

}

}

}The Secret Sauce

Now, let’s take a look at that CreateProvider method in the Enlightenment class. This is the “magic arrow” from my diagram:

What we want to do is determine which assembly contains the platform-specific enlightenment provider, and create an instance of that type.

private static IEnlightenmentProvider CreateProvider()

{

// Starting from our core assembly, determine the matching enlightenment assembly (with the same version/strong name if applicable)

var enlightenmentAssemblyName = new AssemblyName(typeof(IEnlightenmentProvider).Assembly.FullName)

{

Name = "MyLibrary.Enlightenment",

};

// Attempt to load the enlightenment provider from that assembly.

var enlightenmentProviderType = Type.GetType("MyLibrary.Internal.PlatformEnlightenment.EnlightenmentProvider, " + enlightenmentAssemblyName.FullName, false);

if (enlightenmentProviderType == null)

return new DefaultEnlightenmentProvider();

else

return (IEnlightenmentProvider)Activator.CreateInstance(enlightenmentProviderType);

}Distribution Notes

NuGet is my distribution mechanism of choice. With the ability to group dependencies by target frameworks and with full support for portable libraries (including grouping dependencies by portable targets), you have a very flexible system for distributing a portable library. It’s easy to create a single package that contains your portable core along with all its platform enlightenments.

Both the portable core assembly and the appropriate platform enlightenment assembly should be included when the package is installed into a project for a specific platform. Only include the portable core assembly when the package is installed into a portable library project. This enables others to create portable libraries dependent on your portable library; when their portable library is installed into a project for a specific platform, your package will bring in your enlightenment assembly at that time.

Here’s a very simple example, if MyLibrary had a portable core supporting .NET 4.5 and Windows Store, with different enlightenment assemblies for each:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<package>

<metadata>

<id>MyLibrary</id>

</metadata>

<files>

<!-- .NET 4.5 -->

<!-- Core + Enlightenment -->

<file src="MyLibrary\bin\Release\MyLibrary.dll" target="lib\net45" />

<file src="MyLibrary\bin\Release\MyLibrary.xml" target="lib\net45" />

<file src="MyLibrary.Enlightenment (NET45)\bin\Release\MyLibrary.Enlightenment.dll" target="lib\net45" />

<file src="MyLibrary.Enlightenment (NET45)\bin\Release\MyLibrary.Enlightenment.xml" target="lib\net45" />

<!-- Windows Store -->

<!-- Core + Enlightenment -->

<file src="MyLibrary\bin\Release\MyLibrary.dll" target="lib\win8" />

<file src="MyLibrary\bin\Release\MyLibrary.xml" target="lib\win8" />

<file src="MyLibrary.Enlightenment (Win8)\bin\Release\MyLibrary.Enlightenment.dll" target="lib\win8" />

<file src="MyLibrary.Enlightenment (Win8)\bin\Release\MyLibrary.Enlightenment.xml" target="lib\win8" />

<!-- Portable libraries: .NET 4.5, Windows Store -->

<!-- Core, no Enlightenment -->

<file src="MyLibrary\bin\Release\MyLibrary.dll" target="lib\portable-net45+win8" />

<file src="MyLibrary\bin\Release\MyLibrary.xml" target="lib\portable-net45+win8" />

</files>

</package>It’s Best to Be Sure

Our CreateProvider should be able to load the enlightenment in normal situations. But we all know how other developers can mess things up, right? ;) What if they’re doing some funky assembly loading from subdirectories so that we can’t find the enlightenment?

We can provide some level of assurance by allowing a single line of “startup” code. Of course, this is optional; CreateProvider does not need it in most cases, and we always have the default enlightenments to fall back on.

In each of my platform enlightenment assemblies, I define a single method in a normal namespace (i.e., not hidden from the user):

/// Verifies platform enlightenment.

public static class EnlightenmentVerification

{

/// Returns a value indicating whether the correct platform enlightenment provider has been loaded.

public static bool EnsureLoaded()

{

return Enlightenment.Platform is EnlightenmentProvider;

}

}This method simply checks to make sure its platform enlightenment is the one being used. Just to be sure.

Tips

Use as many enlightenments as you need. I have a total of six enlightenments for my AsyncEx library. Some of them are nearly as simple as the “Bob” enlightenment; others are more complex.

If a platform would just use the default enlightenments anyway, then there’s no point in creating a platform enlightenment provider for it.

Only enlighten the behavior you need. My Lazy<T> enlightenment only has one constructor and two properties; it only supports one thread safety mode and is allowed to invoke its factory while holding a lock. This is significantly simpler than the Microsoft Lazy<T>, but my Portable Core doesn’t need any more than that.

I make my default enlightenments accessible to other enlightenment providers (they’re public nested classes). This enables a platform to decide to implement some enlightenments but return the default enlightenment for others.

Most default enlightenments need to use reflection. It’s best to use reflection only on startup and cache delegates for future use. I use the “compile Expression to a delegate” technique described by Eric Lippert in this SO answer. Just be sure to watch your exceptions when doing the reflection!

Speaking of reflection, spend some time thinking about whether you want to upgrade behavior or not. This is particularly true for .NET 4.5, which is an in-place upgrade to .NET 4.0. As one example, I have an exception enlightenment on .NET 4.0 that will upgrade to ExceptionDispatchInfo via reflection if it’s running on .NET 4.5; since the .NET 4.0 equivalent is a hack, I always upgrade if I can. On the other hand, I have a tracing enlightenment on .NET 4.5 using ETW, but the tracing enlightenment on .NET 4.0 will use TraceSource even if .NET 4.5 is present; this ensures the end user always knows where to look for trace output based on their target platform, not what’s available at runtime.

Enlightenment assemblies can be difficult to test if they use reflection for upgrades. Ideally, you would test a combination of target platforms with runtime capabilities, and do that testing for both the platform-specific enlightenments and default enlightenments. Consider a distributed testing system.

If you use enlightenments the way I’ve described in this blog post, keep in mind that they are conceptually singletons. This means that if you’re enlightening a type (e.g., Lazy<T>), you first need to define a portable interface and then have your enlightenment act as a factory.

It’s perfectly fine to have your platform enlightenment assemblies be portable libraries themselves. My AsyncEx library uses the same portable assembly for enlightenment on .NET 4.5 and Windows Store.

If you’re modifying an existing library to have a portable core, you should keep open to refactoring. In particular, if you implement interfaces that aren’t available on some of your target platforms, those types may be a better fit for a “slightly less portable” additional assembly. I did this with the Dataflow types in my AsyncEx library; I have a “fully portable” core (Nito.AsyncEx.dll) and a “less portable” additional assembly (Nito.AsyncEx.Dataflow.dll). This is mostly transparent to users (at compile time) because both assemblies are distributed in the same NuGet package.

References

Daniel Plaisted’s blog post How to Make Portable Class Libraries Work for You.