Announcement: Async Diagnostics

• CommentsIt is with greatest pleasure that I announce the public (pre)release of Async Diagnostics.

Currently, diagnostics can be a bit… difficult… when dealing with async code. In particular, the call stack is not very useful for diagnostics in asynchronous code.

A Brief Digression on Call Stacks and Causality Stacks

I’ll cut to the chase: the call stack is about where you’re going next, not where you came from. This means that you should not look to the call stack to find out how your code got into that situation. What you really want is a “causality stack”.

This is counter-intuitive to many developers because in the synchronous world, the call stack is the causality stack. But in the asynchronous world, they are very different. Eric Lippert has some great SO answers (1, 2) that clarify what the call stack really is.

There’s also a recent MSDN article that explains why call stacks aren’t causality stacks. That article includes a fairly involved way to build causality chains that works for Windows Store applications but does not properly handle fork/join scenarios (e.g., Task.WhenAll).

Introducing Async Diagnostics

You can now download a library into your project from NuGet, follow the simple instructions, and you’ll get asynchronous diagnostic (causality) stacks for all exceptions thrown in (or through) your assembly.

Example

Consider the following example program. It has reasonably realistic asynchronous method usage; the MainAsync method calls the MyMethodAsync method, which is overloaded to allow cancellation. MyMethodAsync in turn spins up a couple of parallel asynchronous tasks and waits for them both to complete. One of these tasks will throw an exception.

using System;

using System.Threading;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

MainAsync(args).Wait();

}

static async Task MainAsync(string[] args)

{

try

{

await MyMethodAsync("I'm an asynchronous exception! Locate me if you can!");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex.ToString());

Console.ReadKey();

}

}

static Task MyMethodAsync(string message)

{

return MyMethodAsync(message, CancellationToken.None);

}

static async Task MyMethodAsync(string message, CancellationToken token)

{

var task1 = Task.Delay(1000);

var task2 = Task.Run(() => { throw new InvalidOperationException(message); }); // (line 33)

await Task.WhenAll(task1, task2);

}

}If you run this program, you’ll see output like this:

System.InvalidOperationException: I'm an asynchronous exception! Locate me if you can!

at Program.<>c__DisplayClass4.<MyMethodAsync>b__3() in e:\work_\projects\ConsoleApplication8\ConsoleApplication8\Program.cs:line 33

at System.Threading.Tasks.Task`1.InnerInvoke()

at System.Threading.Tasks.Task.Execute()

--- End of stack trace from previous location where exception was thrown ---

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.ThrowForNonSuccess(Task task)

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.HandleNonSuccessAndDebuggerNotification(Task task)

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.GetResult()

at Program.<MyMethodAsync>d__6.MoveNext() in e:\work_\projects\ConsoleApplication8\ConsoleApplication8\Program.cs:line 34

--- End of stack trace from previous location where exception was thrown ---

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.ThrowForNonSuccess(Task task)

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.HandleNonSuccessAndDebuggerNotification(Task task)

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.GetResult()

at Program.<MainAsync>d__0.MoveNext() in e:\work_\projects\ConsoleApplication8\ConsoleApplication8\Program.cs:line 16

If you’re familiar with mangled call stacks, you can see from the first entry that the exception was raised from a lambda expression in MyMethodAsync, and you even get the file name and line number. But the real question is: how did the program get in this state? You can often answer that question by answering the closely related questions: what called this method, and what called the calling method, etc? A regular call stack just isn’t sufficient to answer those questions for asynchronous code. You need a causality stack.

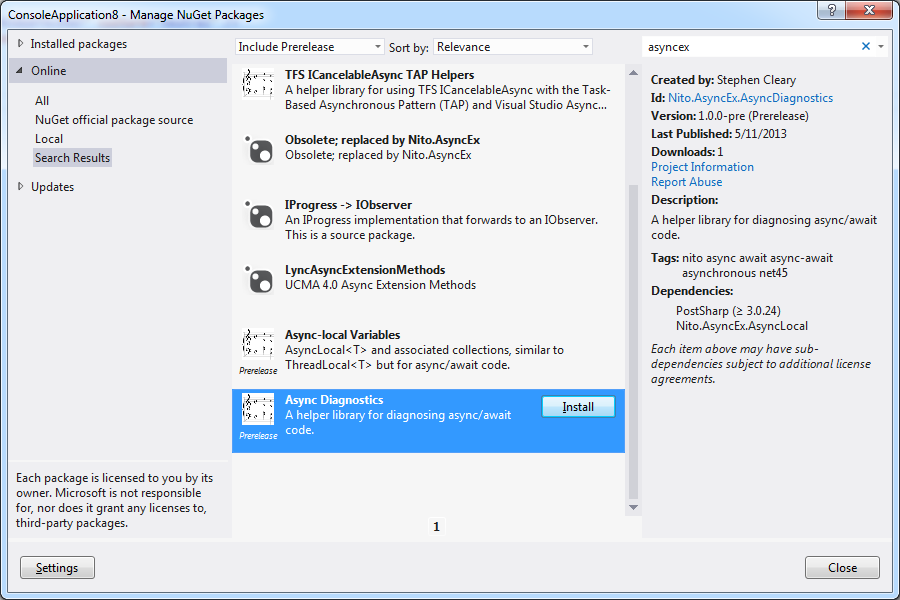

First, add the Nito.AsyncEx.AsyncDiagnostics package to the solution. Be sure to include Prerelease packages:

Once it’s installed, it’ll bring up some installation/usage instructions. First, in one of your source files, apply the AsyncDiagnosticAspect to your assembly. Then, locate the place where you display or log your exceptions, and change ToString to ToAsyncDiagnosticString:

using System;

using System.Threading;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Nito.AsyncEx.AsyncDiagnostics;

[assembly: AsyncDiagnosticAspect]

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

MainAsync(args).Wait();

}

static async Task MainAsync(string[] args)

{

try

{

await MyMethodAsync("I'm an asynchronous exception! Locate me if you can!");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex.ToAsyncDiagnosticString());

Console.ReadKey();

}

}

static Task MyMethodAsync(string message)

{

return MyMethodAsync(message, CancellationToken.None);

}

static async Task MyMethodAsync(string message, CancellationToken token)

{

var task1 = Task.Delay(1000);

var task2 = Task.Run(() => { throw new InvalidOperationException(message); });

await Task.WhenAll(task1, task2);

}

}With these few changes, the new output is the same, except for some additional information printed at the end of the exception stack trace:

System.InvalidOperationException: I'm an asynchronous exception! Locate me if you can!

at Program.<>c__DisplayClass4.<MyMethodAsync>b__3() in e:\work_\projects\ConsoleApplication8\ConsoleApplication8\Program.cs:line 36

at System.Threading.Tasks.Task`1.InnerInvoke()

at System.Threading.Tasks.Task.Execute()

--- End of stack trace from previous location where exception was thrown ---

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.ThrowForNonSuccess(Task task)

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.HandleNonSuccessAndDebuggerNotification(Task task)

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.GetResult()

at Program.<MyMethodAsync>d__6.<MoveNext>z__OriginalMethod() in e:\work_\projects\ConsoleApplication8\ConsoleApplication8\Program.cs:line 37

--- End of stack trace from previous location where exception was thrown ---

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.ThrowForNonSuccess(Task task)

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.HandleNonSuccessAndDebuggerNotification(Task task)

at System.Runtime.CompilerServices.TaskAwaiter.GetResult()

at Program.<MainAsync>d__0.<MoveNext>z__OriginalMethod() in e:\work_\projects\ConsoleApplication8\ConsoleApplication8\Program.cs:line 19

Logical stack:

async Program.MyMethodAsync(String message, CancellationToken token)

Program.MyMethodAsync(String message)

async Program.MainAsync(String[] args)

Program.Main(String[] args)

Now there’s a nice “logical stack” stuck on the end of the exception dump. Unlike the exception call stack, the “logical stack” is actually a causality stack, which is much more useful when debugging asynchronous code. As you can see, the logical stack leads us directly to the location of the exception, and (more importantly) shows how we got there.

Side note: the original exception details are included in ToAsyncDiagnosticString because it does contain some information that is not tracked by the async diagnostic stack. For example, you can look at the top frame in the (synchronous) call stack (Program.<>c__DisplayClass4.<MyMethodAsync>b__3()) and infer that in fact the exception is thrown from a lambda expression and not directly from MyMethodAsync. The synchronous call stack also includes other information such as file names and line numbers that is not (currently) included in the logical stack.

Ready to go one step further? You can tie into the diagnostic stack and add whatever additional data you want:

using System;

using System.Threading;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Nito.AsyncEx.AsyncDiagnostics;

[assembly: AsyncDiagnosticAspect]

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

MainAsync(args).Wait();

}

static async Task MainAsync(string[] args)

{

try

{

await MyMethodAsync("I'm an asynchronous exception! Locate me if you can!");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine(ex.ToAsyncDiagnosticString());

Console.ReadKey();

}

}

static Task MyMethodAsync(string message)

{

using (AsyncDiagnosticStack.Enter(" My message is: " + message))

{

return MyMethodAsync(message, CancellationToken.None);

}

}

static async Task MyMethodAsync(string message, CancellationToken token)

{

var task1 = Task.Delay(1000);

var task2 = Task.Run(() => { throw new InvalidOperationException(message); });

await Task.WhenAll(task1, task2);

}

}And whatever string you give it gets included in the logical stack:

Logical stack:

async Program.MyMethodAsync(String message, CancellationToken token)

My message is: I'm an asynchronous exception! Locate me if you can!

Program.MyMethodAsync(String message)

async Program.MainAsync(String[] args)

Program.Main(String[] args)

Limitations

Async Diagnostics only works on the full .NET framework. So it’s great for WPF or ASP.NET apps, but won’t work for Windows Store, Phone, or Silverlight.

Async Diagnostics works best when you build in Debug mode. In Release mode, the compiler may inline method calls, and then they don’t show up in the logical stack. However, any data you explicitly add to the diagnostic stack will always be included.

Async Diagnostics requires full trust. There is no support for partial trust.

There is a definite runtime impact. Your code will certainly run slower with async diagnostics active. Currently, there is no way to turn async diagnostics on or off at runtime; it is a compile-time-only option. However, you can reduce the runtime impact by only applying AsyncDiagnosticAspect to certain types or namespaces (either by placing the attribute only on the type(s) that need it or by using PostSharp multicasting).

I do attempt to minimize the runtime impact of Async Diagnostics. I do as much processing as possible at compile time. At runtime, I use immutable collections exclusively to maximize memory sharing. However, the runtime impact is still non-trivial. It is possible to leave Async Diagnostics on in production, but you’ll want to do performance testing before making that decision.

AsyncDiagnosticAspect may be applied to assemblies or types. It does not work correctly when multicast onto methods. I expect this will be fixed after PostSharp 3.1 is released.

Async Diagnostics currently requires a paid version of PostSharp (Professional or higher). If you don’t have a PostSharp Professional license, you can evaluate it for free for 45 days. I expect PostSharp 3.1 will allow Async Diagnostics to work with the Community (free) version of PostSharp.

How It Works

It’s actually quite simple. Async Diagnostics is an implicit async context containing a stack of strings (very similar to the example in this blog post) and uses PostSharp to inject pushes and pops into your methods at compile time.

Error Logging Frameworks

Async Diagnostics works by capturing the diagnostic stack at the time the exception is thrown, and placing it on the Exception.Data dictionary. Many error logging frameworks ignore the Data property, but if you Google around you’ll find some solutions for log4net and hacks for ELMAH and nLog. As of this writing, Microsoft’s Enterprise Library is the only logging framework I know of that does include Data values by default.

Call to Action

Please download Async Diagnostics and take it for a spin! I’ve run a number of tests but haven’t tried it on really complex code bases. Let me know (in the AsyncDiagnostics library issues) if it doesn’t work!